This piece of excellent journalism appeared in the New Yorker recently. It describes the nightmarish conditions that Iraqis who collaborate with the US experience and the callous disregard for their safety they face. Entering the Green Zone to carry out duties for the US is fraught with difficulties. A frank memo from the American Embassy in Baghdad to the Secretary of State paints a portrait of Iraqi staff living in fear for their lives. One employee asked to be given press credentials following an incident when a guard read out loudly “Embassy” from her ID card. Such things overheard by the wrong people can lead to death in Iraq. Nor are staff able to be used at “on-screen” events for fear of being recognized.

Iraqis who wish to flee the country find themselves out of luck. Passports issued during the Saddam era have been cancelled by the Iraqi government while those issued after the 2003 invasion were so shoddily produced that no Western or Arab governments are accepting them due to wide-scale forgeries in circulation.

A new series of passports was being printed, but the Ministry of the Interior had ordered only around twenty thousand copies, an Iraqi official told me, far too few to meet the need—which meant that obtaining a valid passport, like buying gas or heating oil, would become subject to black-market influences. In Baghdad, Othman told me that a new passport would cost him six hundred dollars, paid to a fixer with connections at the passport offices. The Ministry of the Interior refused to allow Iraqi Embassies to print the new series, so refugees outside Iraq who needed valid passports would have to return to the country they had fled or pay someone a thousand dollars to do it for them.

The article is bursting with information that allows us to see clearly the depradations facing Iraqis and is well worth the read.

An Iraqi interpreter wears a mask to conceal his identity while he assists a soldier delivering an invitation to an Imam for a meeting with an American colonel. Photograph by James Nachtwey.

On a cold, wet night in January, I met two young Iraqi men in the lobby of the Palestine Hotel, in central Baghdad. A few Arabic television studios had rooms on the upper floors of the building, but the hotel was otherwise vacant. In the lobby, a bucket collected drips of rainwater; at the gift shop, which was closed, a shelf displayed film, batteries, and sheathed daggers covered in dust. A sign from another era read, “We have great pleasure in announcing the opening of the Internet café 24 hour a day. At the business center on the first floor. The management.” The management consisted of a desk clerk and a few men in black leather jackets slouched in armchairs and holding two-way radios.

The two Iraqis, Othman and Laith, had asked to meet me at the Palestine because it was the only place left in Baghdad where they were willing to be seen with an American. They lived in violent neighborhoods that were surrounded by militia checkpoints. Entering and leaving the Green Zone, the fortified heart of the American presence, had become too risky. But even the Palestine made them nervous. In October, 2005, a suicide bomber driving a cement mixer had triggered an explosion that nearly brought down the hotel’s eighteen-story tower. An American tank unit that was guarding the hotel eventually pulled out, leaving security in the hands of Iraqi civilians. It would now be relatively easy for insurgents to get inside. The one comforting thought for Othman and Laith was that, four years into the war, the Palestine was no longer worth attacking.

The Iraqis and I went up to a room on the eighth floor. Othman smoked by the window while Laith sat on one of the twin beds. (The names of most of the Iraqis in this story have been changed for their protection.) Othman was a heavyset doctor, twenty-nine years old, with a gentle voice and an unflappable ironic manner. Laith, an engineer with rimless eyeglasses, was younger and taller, and given to bursts of enthusiasm and displeasure. Othman was Sunni, Laith was Shiite.

It had taken Othman three days to get to the hotel from his house, in western Baghdad. On the way, he was trapped for two nights at his sister’s house, which was in an ethnically mixed neighborhood: gun battles had broken out between Sunni and Shiite militiamen. Othman watched the home of his sister’s neighbor, a Sunni, burn to the ground. Shiite militiamen scrawled the words “Leave or else” on the doors of Sunni houses. Othman was able to leave the house only because his sister’s husband—a Shiite, who was known to the local Shia militias—escorted him out. Othman took a taxi to the house of Laith’s grandfather; from there, he and Laith went to the Palestine, where they enjoyed their first hot water in several weeks.

They had a strong friendship, based on a shared desire. Before the war, they had both longed for the arrival of the Americans, expecting them to change their lives. They had told each other that they would try to work with the foreigners. Othman and Laith were both secular, and despised the extremist militias on each side of Iraq’s civil war, but the ethnic conflict had led them increasingly to quarrel, to the point that one of them—usually Laith—would refuse to speak to the other.

Laith began to describe these strains. “It started when the Americans came with Shia leaders and wanted to give the Shia leadership—”

“And kick out the Sunnis,” Othman interrupted. “You admit this? You were not admitting it before.”

“The Americans don’t want to kick out the Sunnis,” Laith said. “They want to give Shia the power because most Iraqis are Shia.”

“And you believe the Sunnis did not want to participate, right?” Othman said. “The Americans didn’t give them the chance to participate.” He turned to me: “You know I’m not just saying this because I’m a Sunni—”

Laith rolled his eyes. “Whatever.”

“But I think the Shia made the Sunnis feel that they’re against them.”

“This is not the point, who started it,” Laith said heatedly. “Everybody is getting killed, the Shia and the Sunnis.” He paused. “But if we think who started it, I think the Sunnis started it!”

“I think the Shia,” Othman repeated, with calm knowingness. He said to me, “When I feel that I’m pushing too much and he starts to become so angry, I pull the brake.”

Laith had a job with an American organization, affiliated with the National Endowment for Democracy, that encouraged private enterprise in developing countries. Othman had worked with a German group called Architects for People in Need, and then as a translator for foreign journalists. These were coveted jobs, but over time they had become so dangerous that Othman and Laith could talk candidly about their lives with no one except each other.

“I trust him,” Othman said of his friend. “We’ve shared our experiences with foreigners—the good and the bad. We don’t have a secret life when we are together. But when we go out we have to lie.”

Othman’s cell phone rang: a friend was calling from Jordan. “I had a vision that you’ll be killed by the end of the month,” he told Othman. “Get out now, please. You can stay here with me. We’ll live on pasta.” Othman said something reassuring and hung up, but his phone kept ringing, the friend calling back; his vision had made him hysterical.

A string of bad events had given Othman the sense that time was running out for him in Iraq. In November, members of the Mahdi Army—the Shia militia commanded by the radical cleric Moqtada al-Sadr—rounded up Othman’s older brother and several other Sunnis who worked in a shop in a mixed neighborhood. The Sunnis were taken to a local Shia mosque and shot. Othman’s brother was only grazed in the head, but a Shiite soldier noticed that he was still alive and shot him in the eye. Somehow, he survived this, too. Othman found his brother and took him to a hospital for surgery. The hospital—like the entire Iraqi health system—was under the Mahdi Army’s control, and Othman decided that his brother would be safer at their parents’ house. The brother was now blind, deranged, and vengeful, making life unbearable for Othman’s family. A few days later, Othman’s elderly maternal aunts, who were Shia and lived in a majority-Sunni area, were told by Sunni insurgents that they had three days to leave. Othman’s father, a retired Sunni officer, went to their neighborhood and convinced the insurgents that his wife’s sisters were, in fact, Sunnis. And then, one day in January, Othman’s two teen-age brothers, Muhammad and Salim, on whom he doted, failed to come home from school. Othman called the cell phone of Muhammad, who was fifteen. “Is this Muhammad?” he said.

A stranger’s voice answered: “No, I’m not Muhammad.”

“Where is Muhammad?”

“Muhammad is right here,” the stranger said. “I’m looking at him now. We have both of them.”

“Are you joking?”

“No, I’m not. Are you Sunni or Shia?”

Thinking of what had happened to his older brother, Othman lied: “We’re Shia.” The stranger told him to prove it. The boys had left their identity cards at home, for their own safety.

Othman’s mother took the phone, sobbing and begging the kidnapper not to hurt her boys. “We’re going to behead them,” the kidnapper told her. “Choose where you want us to throw the bodies. Or do you prefer us to cut them to pieces for you? We enjoy cutting young boys to pieces.” The man hung up.

After several more phone conversations, Othman realized his mistake: the kidnappers were Sunnis, with Al Qaeda. Shiites are not Muslims, the kidnappers told him—they deserve to be killed. Then they stopped answering the phone. Othman called a friend who belonged to a Sunni political party with ties to insurgents; over the course of the afternoon, the friend got the kidnappers back on the phone and convinced them that the boys were Sunnis. They were released with apologies, along with their money and their phones.

It was the worst day of Othman’s life. He said he would never forget the sound of the stranger’s voice.

Othman began a campaign of burning. He went into the yard or up on the roof of his parents’ house with a jerrican of kerosene and set fire to papers, identity badges, books in English, photographs—anything that might incriminate him as an Iraqi who worked with foreigners. If Othman had to flee Iraq, he wanted to leave nothing behind that might harm him or his family. He couldn’t bring himself to destroy a few items, though: his diaries, his weekly notes from the hospital where he had once worked. “I have this bad habit of keeping everything like memories,” he said.

Most of the people Othman and Laith knew had left Iraq. House by house, Baghdad was being abandoned. Othman was considering his options: move his parents from their house (in an insurgent stronghold) to his sister’s house (in the midst of civil war); move his parents and brothers to Syria (where there was no work) and live with his friend in Jordan (going crazy with boredom while watching his savings dwindle); go to London and ask for asylum (and probably be sent back); stay in Baghdad for six more months until he could begin a scholarship that he’d won, to study journalism in America (or get killed waiting). Beneath his calm good humor, Othman was paralyzed—he didn’t want to leave Baghdad and his family, but staying had become impossible. Every day, he changed his mind.

From the hotel window, Othman could see the palace domes of the Green Zone directly across the Tigris River. “It’s sad,” he told me. “With all the hopes that we had, and all the dreams, I was totally against the word ‘invasion.’ Wherever I go, I was defending the Americans and strongly saying, ‘America was here to make a change.’ Now I have my doubts.”

Laith was more blunt: “Sometimes, I feel like we’re standing in line for a ticket, waiting to die.”

By the time Othman and Laith finished talking, it was almost ten o’clock. We went downstairs and found the hotel restaurant empty, with no light or heat. A waiter in a white shirt and black vest emerged out of the darkness to take our orders. We shivered for an hour until the food came.

There was an old woman at the cash register, with long, dyed-blond hair, a shapeless gown, and a macramé beret that kept falling off her head. I recognized her: she had been the cashier in 2003, when I first came to the Palestine. Her name was Taja, and she had worked at the hotel for twenty-five years. She had the smile of a mad hag.

I asked if there had been any other customers tonight. “My dear, no one,” Taja said, in English. The sight of me seemed to jar loose a bundle of memories. Her brother had gone to New Orleans in 1948 and forgotten all about her. There was music here in the old days, she said, and she sang a few lines from the Spaniels’ “Goodnight, Sweetheart, Goodnight”:

Goodnight, sweetheart,

Well it’s time to go.

I hate to leave you, but I really must say,

Goodnight, sweetheart, goodnight.

When the Americans first came, Taja said, the hotel was full of customers, including marines. She took the exam to work as a translator three times, but kept failing, because the questions were so hard: “The spider is an insect or an animal?” “Water is a beverage or a food?” Who could answer such questions?

Taja smiled at us. “Now all finished,” she said.

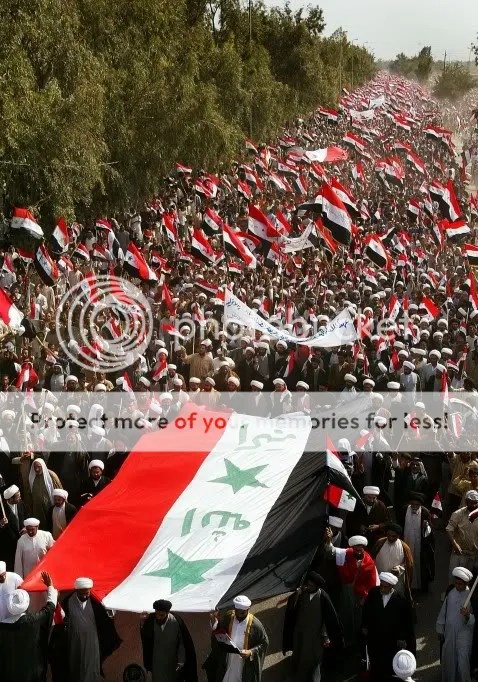

MY TIME WILL COME

Millions of Iraqis, spanning the country’s religious and ethnic spectrum, welcomed the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. But the mostly young men and women who embraced America’s project so enthusiastically that they were prepared to risk their lives for it may constitute Iraq’s smallest minority. I came across them in every city: the young man in Mosul who loved Metallica and signed up to be a translator at a U.S. Army base; the DVD salesman in Najaf whose plans to study medicine were crushed by Baath Party favoritism, and who offered his services to the first American Humvee that entered his city. They had learned English from American movies and music, and from listening secretly to the BBC. Before the war, their only chance at a normal life was to flee the country—a nearly impossible feat. Their future in Saddam’s Iraq was, as the Metallica fan in Mosul put it, “a one-way road leading to nothing.” I thought of them as oddballs, like misunderstood high-school students whose isolation ends when they go off to college. In a similar way, the four years of the war created intense friendships, but they were forged through collective disappointment. The arc from hope to betrayal that traverses the Iraq war is nowhere more vivid than in the lives of these Iraqis. America’s failure to understand, trust, and protect its closest friends in Iraq is a small drama that contains the larger history of defeat.

An interpreter named Firas—he insisted on using his real name—grew up in a middle-class Shia family in a prosperous Baghdad neighborhood. He is a big man in his mid-thirties with a shaved head, and his fierce, heavily ringed eyes provide a glimpse into the reserves of energy that lie beneath his phlegmatic surface. As a young man, Firas was shut out of a government job by his family’s religious affiliation and by his lack of connections. He wasted his twenties in a series of petty occupations: selling cigarettes wholesale; dealing in spare parts; peddling books on Mutanabi Street, in old Baghdad. Books, more than anything, shaped Firas’s passionately melancholy character. As a young man, he kept a credo on his wall in English and Arabic: “Be honest without the thought of Heaven or Hell.” He was particularly impressed by “The Outsider,” a 1956 philosophical work by the British existentialist Colin Wilson. “He wrote about the ‘non-belonger,’ ” Firas explained. Firas felt like an exile in his own land, but, he recalled, “There was always this sound in the back of my head: the time will come, the change will come, my time will come. And when 2003 came, I couldn’t believe how right I was.”

Overnight, everything was new. Americans, whom he had seen only in movies, rolled through the streets. Men who had been silent all their lives cursed Saddam in front of their neighbors. The fall of the regime revealed traits that Iraqis had kept hidden: the greed that drove some to loot, the courage that made others stay on the job. Firas felt a lifelong depression lift. “The first thing I learned about myself was that I can make things happen,” he said. “When you feel that you are an outcast, you don’t really put an effort in anything. But after the war I would run here and there, I would kill myself, I would focus on one thing and not stop until I do it.”

Thousands of Iraqis converged on the Palestine Hotel and, later, the Green Zone, in search of work with the Americans. In the chaos of the early days, a demonstrable ability to speak English—sometimes in a chance encounter with a street patrol—was enough to get you hired by an enterprising Marine captain. Firas began working in military intelligence. Almost all the Iraqis who were hired became interpreters, and American soldiers called them “terps,” often giving them nicknames for convenience and, later, security (Firas became Phil). But what the Iraqis had to offer went well beyond linguistic ability: each of them was, potentially, a cultural adviser, an intelligence officer, a policy analyst. Firas told the soldiers not to point with their feet, not to ask to be introduced to someone’s sister. Interpreters assumed that their perspective would be valuable to foreigners who knew little or nothing of Iraq.

Whenever I asked Iraqis what kind of government they had wanted to replace Saddam’s regime, I got the same answer: they had never given it any thought. They just assumed that the Americans would bring the right people, and the country would blossom with freedom, prosperity, consumer goods, travel opportunities. In this, they mirrored the wishful thinking of American officials and neoconservative intellectuals who failed to plan for trouble. Almost no Iraqi claimed to have anticipated videos of beheadings, or Moqtada al-Sadr, or the terrifying question “Are you Sunni or Shia?” Least of all did they imagine that America would make so many mistakes, and persist in those mistakes to the point that even fair-minded Iraqis wondered about ulterior motives. In retrospect, the blind faith that many Iraqis displayed in themselves and in America seems naïve. But, now that Iraq’s demise is increasingly regarded as foreordained, it’s worth recalling the optimism among Iraqis four years ago.

Ali, an interpreter in Baghdad, spent his childhood in Pennsylvania and Oklahoma, where his father was completing his graduate studies. In 1987, when Ali was eleven and his father was shortly to get his green card, the family returned to Baghdad for a brief visit. But it was during the war with Iran, and the authorities refused to let them leave again. Ali had to learn Arabic from scratch. He grew up in Ghazaliya, a Baathist stronghold in western Baghdad where Shia families like his were rare. Iraq felt like a prison, and Ali considered his American childhood a paradise lost.

In 2003, soon after the arrival of the Americans, soldiers in his neighborhood persuaded him to work as an interpreter with the 82nd Airborne Division. He wore a U.S. Army uniform and a bandanna, and during interrogations he used broken Arabic in order to make prisoners think he was American. Although the work was not yet dangerous, an instinct led him to mask his identity and keep his job to himself around the neighborhood. Ali found that, although many soldiers were friendly, they often ignored information and advice from their Iraqi employees. Interpreters would give them names of insurgents, and nothing would happen. When Ali suggested that soldiers buy up locals’ rocket-propelled grenade launchers so that they would not fall into the hands of insurgents, he was disregarded. When interpreters drove onto the base, their cars were searched, and at the end of their shift they would sometimes find their car doors unlocked or a mirror broken—the cars had been searched again. “People came with true faces to the Americans, with complete loyalty,” Ali said. “But, from the beginning, they didn’t trust us.”

Ali initially worked the night shift at a base in his neighborhood and walked home by himself after midnight. In June, 2003, the Americans mounted a huge floodlight at the front gate of the base, and when Ali left for home the light projected his shadow hundreds of feet down the street. “It’s dangerous,” he told the soldiers at the gate. “Can’t you turn it off when we go out?”

“Don’t be scared,” the soldiers told him. “There’s a sniper protecting you all the way.”

A couple of weeks later, one of Ali’s Iraqi friends was hanging out with the snipers in the tower, and he thanked them. “For what?” the snipers asked. For looking out for us, Ali’s friend said. The snipers didn’t know what he was talking about, and when he told them they started laughing.

“We got freaked out,” Ali said. The message was clear: You Iraqis are on your own.

A PERSON IN BETWEEN

The Arabic for “collaborator” is aameel—literally, “agent.” Early in the occupation, the Baathists in Ali’s neighborhood, who at first had been cowed by the Americans’ arrival, began a shrewd whispering campaign. They told their neighbors that the Iraqi interpreters who went along on raids were feeding the Americans false information, urging the abuse of Iraqis, stealing houses, and raping women. In the market, a Baathist would point at an Iraqi riding in the back of a Humvee and say, “He’s a traitor, a thug.” Such rumors were repeated often enough that people began to believe them, especially as the promised benefits of the American occupation failed to materialize. Before long, Ali told me, the Baathists “made the reputation of the interpreter very, very low—worse than the Americans’.”

There was no American campaign to counter the word on the street; there wasn’t even a sense that these subversive rumors posed a serious threat. “Americans are living in another world,” Ali said. “There’s an Iraqi saying: ‘He’s sleeping and his feet are baking in the sun.’ ” The U.S. typically provided interpreters with inferior or no body armor, allowing the Baathists to make a persuasive case that Americans treated all Iraqis badly, even those who worked for them.

“The Iraqis aren’t trusting you, and the Americans don’t trust you from the beginning,” Ali said. “You became a person in between.”

Firas met the personal interpreter of L. Paul Bremer III, the head of the Coalition Provisional Authority—which governed Iraq for fourteen months after the invasion—in the fall of 2003. Soon, Firas had secured a privileged view of official America, translating documents at the Republican Palace, in the Green Zone.

He liked most of the American officials who came and went at the palace. Even when he saw colossal mistakes at high levels—for example, Bremer’s decision to abolish the Iraqi Army—Firas admired his new colleagues, and believed that they were helping to create institutions that would lead to a better future. And yet Firas kept being confronted by fresh ironies: he had less authority than any of the Americans, although he knew more about Iraq; and the less that Americans knew about Iraq the less they wanted to hear from him, especially if they occupied high positions.

One day, Firas accompanied one of Bremer’s top political advisers to a meeting with an important Shiite cleric. The cleric’s mosque, the Baratha, is an ancient Shiite bastion, and Firas, whose family came from the holy city of Najaf, knew a great deal about the mosque and the cleric. On the way, the adviser asked, “Is this a mosque or a shrine or what?” Firas said, “It’s the Baratha mosque,” and he started to explain its significance, but the adviser cut him short: “O.K., got it.” They went into the meeting with the cleric, who was from a hard-line party backed by Tehran but who spoke as if he represented the views of all Iraqis. He didn’t represent the views of many people Firas knew, and, given the chance, Firas could have told the adviser that the mosque and its Imam had a history of promoting Shia nationalism. “There were a million comments in my head,” Firas recalled. “Why the hell was he paying so much attention to this Imam?”

Bremer and his advisers—Scott Carpenter, Meghan O’Sullivan, and Roman Martinez—were creating an interim constitution and negotiating the transfer of power to Iraqis, but they did not speak Arabic and had no background in the Middle East. The Iraqis they spent time with were, for the most part, returned exiles with sectarian agendas. The Americans had little sense of what ordinary Iraqis were experiencing, and they seemed oblivious of a readily available source of knowledge: the Iraqi employees who had lived in Baghdad for years, and who went home to its neighborhoods every night. “These people would consider themselves too high to listen to a translator,” Firas said. “Maybe they were interested more in telling D.C. what they want to hear instead of telling them what the Iraqis are saying.”

Later, when the Coalition Provisional Authority was replaced by the U.S. Embassy, and political appointees gave way to career diplomats, Firas found himself working for a different kind of American. The Embassy’s political counsellor, Robert Ford, his deputy, Henry Ensher, and a younger official in the political section, Jeffrey Beals, spoke Arabic, had worked extensively in the region, and spent most of their time in Baghdad talking to a range of Iraqis, including extremists. They gave Firas and other “foreign-service nationals” more authority, encouraging them to help write reports on Iraqi politics that were sometimes forwarded to Washington. Beals would be interviewed in Arabic on Al Jazeera and then endure a thorough critique by an Iraqi colleague—Ahmed, a tall, handsome Kurdish Shiite who lived just outside Sadr City, and who was obsessed with Iraqi politics. When Firas, Ali, and Ahmed visited New York during a training trip, Beals’s brother was their escort.

Beals quit the foreign service after almost two years in Iraq and is now studying history at Columbia University. He said that, with Americans in Baghdad coming and going every six or twelve months, “the lowest rung on your ladder ends up being the real institutional memory and repository of expertise—which is always a tension, because it’s totally at odds with their status.” The inversion of the power relationship between American officials and Iraqi employees became more dramatic as the dangers increased and American civilians lost almost all mobility around Baghdad. Beals said, “There aren’t many people with pro-American eyes and the means to get their message across who can go into Sadr City and tell you what’s happening day to day.”

BADGES

On the morning of January 18, 2004, a suicide truck bomber detonated a massive payload amid a line of vehicles waiting to enter the Green Zone by the entry point known as the Assassins’ Gate. Most Iraqis working in the Green Zone knew someone who died in the explosion, which incinerated twenty-five people. Ali was hit by the blowback but was otherwise uninjured; two months later, he narrowly escaped an assassination attempt while driving to work. Throughout 2004, the murder of interpreters and other Iraqi employees became increasingly commonplace. Seven of Ali’s friends who worked with the U.S. military were killed, which prompted him to leave the Army and take a job at the Embassy.

In Mosul, insurgents circulated a DVD showing the decapitations of two military interpreters. American soldiers stationed there expressed sympathy to their Iraqi employees, but, one interpreter told me, there was “no real reaction”: no offer of protection, in the form of a weapons permit or a place to live on base. He said, “The soldiers I worked with were friends and they felt sorry for us—they were good people—but they couldn’t help. The people above them didn’t care. Or maybe the people above them didn’t care.” This story repeated itself across the country: Iraqi employees of the U.S. military began to be kidnapped and killed in large numbers, and there was essentially no American response. Titan Corporation, of Chantilly, Virginia, which until December held the Pentagon contract for employing interpreters in Iraq, was notorious among Iraqis for mistreating its foreign staff. I spoke with an interpreter who was injured in a roadside explosion; Titan refused to compensate him for the time he spent recovering from second-degree burns on his hands and feet. An Iraqi woman working at an American base was recognized by someone she had known in college, who began calling her with death threats. She told me that when she went to the Titan representative for help he responded, “You have two choices: move or quit.” She told him that if she quit and stayed home, her life would be in danger. “That’s not my business,” the representative said. (A Titan spokesperson said, “The safety and welfare of all employees, including, of course, contract workers, is the highest priority.”)

A State Department official in Iraq sent a cable to Washington criticizing the Americans’ “lackadaisical” attitude about helping Iraqi employees relocate. In an e-mail to me, he said, “Most of them have lived secret lives for so long that they are truly a unique ‘homeless’ population in Iraq’s war zone—dependent on us for security and not convinced we will take care of them when we leave.” It’s as if the Americans never imagined that the intimidation and murder of interpreters by other Iraqis would undermine the larger American effort, by destroying the confidence of Iraqis who wanted to give it support. The problem was treated as managerial, not moral or political.

One day in January, 2005, Riyadh Hamid, a Sunni father of six from the Embassy’s political section, was shot to death as he left his house for work. When Firas heard the news at the Embassy, he was deeply shaken: he, Ali, or Ahmed could be next. But he never thought of quitting. “At that time, I believed more in my cause, so if I die for it, let it be,” he said.

Americans and Iraqis at the Embassy collected twenty thousand dollars in private donations for Hamid’s widow. At first, the U.S. government refused to pay workmen’s compensation, because Hamid had been travelling between home and work and was not technically on the job when he was killed. (Eventually, compensation was approved.) A few days after the murder, Robert Ford, the political counsellor, arranged a conversation between Ambassador John Negroponte and the Iraqis from the political section, whom the Ambassador had never met. The Iraqis were escorted into a room in a secure wing of the Embassy’s second floor.

Negroponte had barely expressed his condolences when Firas, Ahmed, and their colleagues pressed him with a single request. They wanted identification that would allow them to enter the Green Zone through the priority lane that Americans with government clearance used, instead of having to wait every morning for an hour or two in a very long line with every other Iraqi who had business in the Green Zone. This line was an easy target for suicide bombers and insurgent lookouts (known in Iraq as alaasa—“chewers”). Iraqis at the Embassy had been making this request for some time, without success. “Our problem is badges,” the Iraqis told the Ambassador.

Negroponte sent for the Embassy’s regional security officer, John Frese. “Here’s the man who is responsible for badges,” Negroponte said, and left.

According to the Iraqis, they asked Frese for green badges, which were a notch below the official blue American badges. These allowed the holder to enter through the priority lane and then be searched inside the gate.

“I can’t give you that,” Frese said.

“Why?”

“Because it says ‘Weapon permit: yes.’ ”

“Change the ‘yes’ to ‘no’ for us.”

Frese’s tone was peremptory: “I can’t do that.”

Ahmed made another suggestion: allow the Iraqis to use their Embassy passes to get into the priority lane. Frese again refused. Ahmed turned to one of his colleagues and said, in Arabic, “We’re blowing into a punctured bag.”

“My top priority is Embassy security, and I won’t jeopardize it, no matter what,” Frese told them, and the Iraqis understood that this security did not extend to them—if anything, they were part of the threat.

After the meeting, a junior American diplomat who had sat through it was on the verge of tears. “This is what always calmed me down,” Firas said. “I saw Americans who understand me, trust me, believe me, love me. This is what always kept my rage under control and kept my hope alive.”

When I recently asked a senior government official in Washington about the badges, he insisted, “They are concerns that have been raised, addressed, and satisfactorily resolved. We acted extremely expeditiously.” In fact, the matter was left unresolved for almost two years, until late 2006, when verbal instructions were given to soldiers at the gates of the Green Zone to let Iraqis with Embassy passes into the priority lane—and even then individual soldiers, among whom there was rapid turnover, often refused to do so.

Americans and Iraqis recalled the meeting as the moment when the Embassy’s local employees began to be disenchanted. If Negroponte had taken an interest, he could have pushed Frese to change the badges. But a diplomat doesn’t rise to Negroponte’s stature by busying himself with small-bore details, and without his directive the rest of the bureaucracy wouldn’t budge.

In Baghdad, the regional security officer had unusual power: to investigate staff members, to revoke clearances, to block diplomats’ trips outside the Green Zone. The word “security” was ubiquitous—a “magical word,” one Iraqi said, that could justify anything. “Saying no to the regional security officer is a dangerous thing,” according to a second former Embassy official, who occasionally did say no in order to be able to carry out his job. “You’re taking a lot of responsibility on yourself.” Although Iraqi employees had been vetted with background checks and took regular lie-detector tests, a permanent shadow of suspicion lay over them because they lived outside the Green Zone. Firas once attended a briefing at which the regional security officer told newly arrived Americans that no Iraqi could be trusted.

The reminders were constant. Iraqi staff members were not allowed into the gym or the food court near the Embassy. Banned from the military PX, they had to ask an American supervisor to buy them a pair of sunglasses or underwear. These petty humiliations were compounded by security officers who easily crossed the line between vigilance and bullying.

One day in late 2004, Laith, who had never given up hope of working for the American Embassy, did well on an interview in the Green Zone and was called to undergo a polygraph. After he was hooked up to the machine, the questions began: Have you ever lied to your family? Do you know any insurgents? At some point, he thought too hard about his answer; when the test was over, the technician called in a security officer and shouted at Laith: “Do you think you can fuck with the United States? Who sent you here?” Laith was hustled out to the gate, where the technician promised to tell his employers at the National Endowment for Democracy to fire him.

“That was the first time I hated the Americans,” Laith said.

CORRIDORS OF POWER

In January, 2005, Kirk Johnson, a twenty-four-year-old from Illinois, arrived in Baghdad as an information officer with the United States Agency for International Development. He came from a patriotic family that believed in public service; his father was a lawyer whose chance at an open seat in Congress, in 1986, was blocked when the state Republican Party chose a former wrestling coach named Dennis Hastert to run instead. Johnson, an Arabic speaker, was studying Islamist thought as a Fulbright scholar in Cairo when the war began; when he arrived in Baghdad, he became one of U.S.A.I.D.’s few Arabic-speaking Americans in Iraq.

Johnson, who is rangy, earnest, and baby-faced, thought that he was going to help America rebuild Iraq, in a mission that was his generation’s calling. Instead, he found a “narcotic” atmosphere in the Green Zone. Surprisingly few Americans ever ventured outside its gates. A short drive from the Embassy, at the Blue Star Café—famous for its chicken fillet and fries—contractors could be seen, in golf shirts, khakis, and baseball caps, enjoying a leisurely lunch, their Department of Defense badges draped around their necks. At such moments, it was hard not to have uncharitable thoughts about the war—that Americans today aren’t equipped for something of this magnitude. Iraq is that rare war in which people put on weight. An Iraqi woman at the Embassy who had seen many Americans come and go—and revered a few of them—declared that seventy per cent of them were “useless, crippled,” avoiding debt back home or escaping a bad marriage. I met an American official who, during one year, left the Green Zone less than half a dozen times; unlike many of his colleagues, he understood this to be a problem.

The deeper the Americans dug themselves into the bunker, the harder they tried to create a sense of normalcy, resulting in what Johnson called “a bizarre arena of paperwork and booze.” There were karaoke nights and volleyball leagues, the Baghdad Regatta, and “Country Night—One Howdy-Doody Good Time.” Halliburton, the defense contractor, hosted a Middle Eastern Night. The cubicles in U.S.A.I.D.’s new Baghdad office building, Johnson discovered, were exactly the same as the cubicles at its headquarters in Washington. The more chaotic Iraq became, the more the Americans resorted to bureaucratic gestures of control. The fact that it took five signatures to get Adobe Acrobat installed on a computer was strangely comforting.

Johnson learned that Iraqis were third-class citizens in the Green Zone, after Americans and other foreigners. For a time, Americans were ordered to wear body armor while outdoors; when Johnson found out that Iraqi staff members hadn’t been provided with any, he couldn’t bear to wear his own around them. Superiors eventually ordered him to do so. “If you’re still properly calibrated, it can be a shameful sort of existence there,” Johnson said. “It takes a certain amount of self-delusion not to be brought down by it.”

In October, 2004, two bombs killed four Americans and two Iraqis at a café and a shopping center inside the Green Zone, fuelling the suspicion that there were enemies within. The Iraqi employees became perceived as part of an undifferentiated menace. They also induced a deeper, more elusive form of paranoia. As Johnson put it, “Not that we thought they’d do us bodily harm, but they represented the reality beyond those blast walls. You keep your distance from these Iraqis, because if you get close you start to discover it’s absolute bullshit—the lives of people in Baghdad aren’t safer, in spite of our trend lines or ginned-up reports by contractors that tell you everything is going great.”

After eight months in the Green Zone, Johnson felt that the impulse which had originally made him volunteer to work in Iraq was dying. He got a transfer to Falluja, to work on the front lines of the insurgency.

The Iraqis who saw both sides of the Green Zone gates had to be as alert as prey in a jungle of predators. Ahmed, the Kurdish Shiite, had the job of reporting on Shia issues, and his feel for the mood in Sadr City was crucial to the political section. When a low-flying American helicopter tore a Shia religious flag off a radio tower, Ahmed immediately picked up on rumors, started by the Mahdi Army, that Americans were targeting Shia worshippers. His job required him to seek contact with members of Shiite militias, who sometimes reacted to him with suspicion. He once went to a council meeting near Sadr City that had been called to arrange a truce between the Americans and the Mahdi Army so that garbage could be cleared from the streets. A council member confronted Ahmed, demanding to know who he was. Ahmed responded, “I’m from a Korean organization. They sent me to find out what solution you guys come up with. Then we’re ready to fund the cleanup.” At another meeting, he identified himself as a correspondent from an Iraqi television network. No one outside his immediate family knew where he worked.

Ahmed took two taxis to the Green Zone, then walked the last few hundred yards, or drove a different route every day. He carried a decoy phone and hid his Embassy phone in his car. He had always loved the idea of wearing a jacket and tie in an official job, but he had to keep them in his office at the Embassy—it was impossible to drive to work dressed like that. Ahmed and the other Iraqis entered code names for friends and colleagues into their phones, in case they were kidnapped. Whenever they got a call in public from an American contact, they answered in Arabic and immediately hung up. They communicated mostly by text message. They never spoke English in front of their children. One Iraqi employee slept in his car in the Green Zone parking lot for several nights, because it was too dangerous to go home.

Baghdad, which has six million residents, at least provided the cover of anonymity. In a small Shia city in the south, no one knew that a twenty-six-year-old Shiite named Hussein was working for the Americans. “I lie and lie and lie,” he said. He acted as a go-between, carrying information between the U.S. outpost, the local government, the Shia clergy, and the radical Sadrists. The Americans would send him to a meeting of clerics with a question, such as whether Iranian influence was fomenting violence. Instead of giving a direct answer, the clerics would demand to know why thousands of American soldiers were unable to protect Shia travellers on a ten-kilometre stretch of road. Hussein would take this back to the Americans and receive a “yes-slash-no kind of answer: We will take it up, we’ll get back to them soon—the soon becomes never.” In this way, he was privy to both sides of the deepening mutual disenchantment. The fact that he had no contact with Sunnis did not make Hussein feel any safer: by 2004, Shia militias were also targeting Iraqis who worked with Americans.

As a youth, Hussein was an overweight misfit obsessed with Second World War documentaries, and now he felt grateful to the Americans for freeing him from Saddam’s tyranny. He also took a certain pride and pleasure in carrying off his risky job. “I’m James Bond, without the nice lady or the famous gadgets,” he said. He worked out of a series of rented rooms, seldom going out in public, relying on his cell phone and his laptop, keeping a small “runaway bag” with him in case he needed to leave quickly (a neighbor once informed him that some strangers had asked who lived there, and Hussein moved out the same day). Every few days, he brought his laundry to his parents’ house. He stopped seeing friends, and his life winnowed down to his work. “You have to live two separate lives, one visible and the other one invisible,” Hussein told me when we spoke in Erbil. (He insisted on meeting in Kurdistan, because there was nowhere else in Iraq that he felt safe being seen with me.) “You have to always be aware of the car behind you. When you want to park, you make sure that the car passes you. You’re always afraid of a person staring at you in an abnormal way.”

He received three threats. The first was graffiti written across his door, the second a note left outside his house. Both said, “Leave your job or we’ll kill you.” The third came in December, after American soldiers killed a local militia leader who had been one of Hussein’s most important contacts. A friend approached Hussein and conveyed an anonymous warning: “You better not have anything to do with this event. If you do, you’ll have to take the consequences.” Since Hussein was known to have interpreted for American soldiers at the start of the war, he said, his name had long been on the Mahdi Army’s blacklist. It was not just frightening but also embarrassing to be a suspect in the militia leader’s death; it undermined Hussein in the eyes of his carefully cultivated contacts. “The stamp that comes to you will never go—you will stay a spy,” he said.

He informed his American supervisor, as he had after the previous two threats. And the reply was the same: lie low, take a leave with pay. Hussein had warm feelings for his supervisor, but he wanted a transfer to another country in the Middle East or a scholarship offer to the U.S.—some tangible sign that his safety mattered to them. None was forthcoming. Once, in April, 2004, when the Mahdi Army had overrun Coalition posts all over southern Iraq, he had asked to be evacuated along with the Americans and was refused; his pride wouldn’t let him ask again. Soon after Hussein received his third threat, his supervisor left Iraq.

“You are now belonging to no side,” Hussein said.

In June, 2006, with kidnappings and sectarian killings out of control in Baghdad, the number of Iraqis working in the Embassy’s public-affairs section dropped from nine to four; most of those who quit fled the country. The Americans began to replace them with Jordanians. The switch was deeply unpopular with the remaining Iraqis, who understood that it involved the fundamental issue of trust: Jordanians could be housed in the Green Zone without fear (Iraqis could secure temporary housing for only a limited time); Jordanians were issued badges that allowed them into the Embassy without being searched; they weren’t subject to threat and blackmail, because they lived inside the Green Zone. In every way, Jordanians were easier to deal with. But they also knew nothing about Iraq. One former Embassy official, who considered the new policy absurd, lamented that a Jordanian couldn’t possibly understand that the term “February 8th mustache,” say, referred to the 1963 Baathist coup.

In the past year, the U.S. government has lost a quarter of its two hundred and six Iraqi employees, and many have been replaced by Jordanians. Not long ago, the U.S. began training citizens of the Republic of Georgia to fill the jobs of Iraqis in Baghdad. “I don’t know why it’s better to have these people flown into Iraq and secure them in the Green Zone,” a State Department official said. “Why wouldn’t we bring Iraqis into the Green Zone and give them housing and secure them?” He added, “We’re depriving people of jobs and we’re getting them whacked. It’s not a pretty picture.”

On June 6th, amid the exodus of Iraqis from the public-affairs section, an Embassy official sent a six-page cable to Washington whose subject line read “Public Affairs Staff Show Strains of Social Discord.” The cable described the nightmarish lives of the section’s Iraqi employees and the sectarian tensions rising among them. It was an astonishingly candid report, perhaps aimed at forcing the State Department to confront the growing disaster. The cable was leaked to the Washington Post and briefly became a political liability. One sentence has stuck in my mind: “A few staff members approached us to ask what provisions we would make for them if we evacuate.”

I went to Baghdad in January partly because I wanted to find an answer to this question. Were there contingency plans for Iraqis, and, if so, whom did they include, and would the Iraqis have to wait for a final American departure? Would any Iraqis be evacuated to the U.S.? No one at the Embassy was willing to speak on the record about Iraqi staff, except an official spokesman, Lou Fintor, who read me a statement: “Like all residents of Baghdad, our local employees must attempt to maintain their daily routines despite the disruptions caused by terrorists, extremists, and criminals. The new Iraqi government is taking steps to improve the security situation and essential services in Baghdad. The Iraq security forces, in coördination with coalition forces, are now engaged in a wide-range effort to stabilize the security situation in Baghdad. . . . President Bush strongly reaffirmed our commitment to work with the government of Iraq to answer the needs of all Iraqis.”

I was granted an interview with two officials, who refused to be named. One of them consulted talking points that catalogued what the Embassy had done for Iraqi employees: a Thanksgiving dinner, a recent thirty-five-per-cent salary increase. Housing in the Green Zone could be made available for a week at a time in critical cases, I was told, though most Iraqis didn’t want to be apart from their families. When I asked about contingency plans for evacuation, the second official refused to discuss it on security grounds, but he said, “If we reach that point and have people in danger, the Ambassador would go to the Secretary of State and ask that they be evacuated, and I think they would do it.” The department was reviewing the possibility of issuing special immigrant visas.

To receive this briefing, I had passed through three security doors into the Embassy’s classified section, where there were no Iraqis and no natural light; it seemed as if every molecule of Baghdad air had been sealed off behind the last security door. The Embassy officials struck me as decent, overworked people, yet I left the interview with a feeling of shame. The problem lay not with the individuals but with the institution and, beyond that, with the politics of the American project in Iraq, which from the beginning has been conducted under the illusion that controlling the message mattered more than the reality. A former official at the Embassy told me, “When we say that the corridors of power are insulated, is it that the officials aren’t receiving the information, or is it because the construct under which they’re operating doesn’t even allow them to absorb it?” To admit that Iraqis who work with Americans need to be evacuated would blow a hole in the Administration’s version of the war.

Several days after the interview at the Embassy, I had a more frank conversation with an official there. “I don’t know if it’s fair to say, ‘You work at an embassy of a foreign country, so that country has to evacuate you,’ ” he said. “Do the Australians have a plan? Do the Romanians? The Turks? The British?” He added, “If I worked at the Hungarian Embassy in Washington, would the Hungarians evacuate me from the United States?”

When I mentioned these remarks to Othman, he asked, “Would the Americans behead an American working at the Hungarian Embassy in Washington?”

THE HEARTS OF YOUR ALLIES

In the summer of 2006, Iraqis were fleeing the country at the rate of forty thousand per month. The educated middle class of Baghdad was decamping to Jordan and Syria, taking with them the skills and the more secular ideas necessary for rebuilding a destroyed society, leaving the city to the religious militias—eastern Baghdad was controlled by the poor and increasingly radical Shia, the western districts dominated by Sunni insurgents. House by house, the capital was being ethnically cleansed.

By that time, Firas, Ali, and Ahmed had been working with the Americans for several years. Their commitment and loyalty were beyond doubt. Just going to work in the morning required an extraordinary ability to disregard danger. Panic, Firas realized, could trap you: when the threat came, you felt you were a dead man no matter where you turned, and your mind froze and you sat at home waiting for them to come for you. In order to function, Firas simply blocked out the fear. “My friends at work became the only friends I have,” he said. “My entertainment is at work, my pleasure is at work, everything is at work.” Firas and his friends never imagined that the decision to leave Iraq would be forced on them not by the violence beyond the Green Zone but from within the Embassy itself.

After the bombing of the gold-domed Shia mosque in Samarra that February, Sadr City had become the base for the Mahdi Army’s roving death squads. Ahmed’s neighborhood fell under their complete control, and his drive to work took him through numerous unfriendly—and thorough—militia checkpoints. Strangers began to ask about him. A falafel vender in Sadr City whose stall was often surrounded by Mahdi Army alaasa warned Ahmed that his name had come up. On two occasions, people he scarcely knew approached him and expressed concern about his well-being. One evening, an American official named Oliver Moss, with whom Ahmed was close, walked him out of the Embassy to the parking lot and said, “Ahmed, I know you work for us, but if something happens to you we won’t be able to do anything for you.” Ahmed asked for a cot in a Green Zone trailer and was given the yes/no answer—equal parts personal sympathy and bureaucratic delay—which sometimes felt worse than a flat refusal. The chaos in Baghdad had created a landgrab for Green Zone accommodations, and the Iraqi government was distributing coveted apartments to friends of the political parties while evicting Iraqis who worked with the Americans. The interpreters were distrusted and despised even by officials of the new government that the Americans had helped bring to power.

In April, a Shiite member of the parliament asked Ahmed to look into the status of a Mahdi Army member who had been detained by the Americans. Iraqis at the Embassy sometimes used their office to do small favors for their compatriots; such gestures reminded them that they were serving Iraq as well as America. But Ahmed sent his inquiry through the wrong channel. His supervisor was on leave in the U.S., and so he sent an e-mail to a reserve colonel in the political section. The colonel refused to provide him with any information, and a couple of weeks later, in May, Ahmed was summoned to talk to an agent from the regional security office.

To the Iraqis, a summons of this type was frightening. Ahmed and his friends had seen several colleagues report to the regional security office and never appear at their desks again, with no explanation; one had been turned over to the Iraqi police and was jailed for several weeks. “Don’t go. They’re going to arrest you,” Ali told Ahmed. “Just quit. It’s not worth it.” Ahmed did not listen.

The agent, Barry Hale, who carried a Glock pistol, questioned Ahmed for an hour about his contacts with Sadrists. The notion that Ahmed’s job required him to have contact with the Mahdi Army seemed foreign to Hale, as did the need to have well-informed Iraqis in the political section of the Embassy. According to an American official close to the case, Hale had a general distrust of Iraqis and wanted to replace them with Jordanians. Another official spoke of a “paranoia partly founded on ignorance. If Ahmed wanted to hurt an American, he could have done it very easily in the three years he worked with us.”

Robert Ford, the political counsellor, spoke to top officials at the Embassy to insure that Ahmed—whom several Americans described as the best Iraqi employee they had worked with—would be “counselled” but not fired. Everyone assumed that the case was closed. But over the summer, after Ford’s service in Baghdad ended, Hale started to pursue Ahmed again. “It was a witch hunt,” one of the officials said. “They wanted to fire him and they were just looking for a reason. They decided he was a threat.” The irony of his situation was not lost on Ahmed: he was suspected of giving information to a militia that would kill him instantly if they knew where he worked.

In late July, Hale summoned Ahmed again. On Hale’s desk, Ahmed saw a thick file marked “Secret,” next to a pair of steel handcuffs.

“Did you ever get a phone call from the Mahdi Army?” Hale asked.

“I’ll be lucky if I get a phone call from them,” Ahmed replied. “My supervisor will be very happy.”

The interrogation came down to one point: Hale insisted that Ahmed had misled him by saying that the reserve colonel had “never answered” Ahmed’s inquiry, when in fact the colonel had sent back an e-mail asking who had given Ahmed the detainee’s name. Ahmed hadn’t considered this an answer to his question about the detainee’s status, and therefore hadn’t mentioned it to Hale. This was his undoing.

When Ahmed returned to his desk, Firas and Ali embraced him and congratulated him on escaping detention. Meanwhile, lower-ranking Embassy officials began frantically calling and e-mailing colleagues in Washington, some of whom tried to intervene on Ahmed’s behalf. But by then it was too late. The new Ambassador, Zalmay Khalilzad, and his deputy were out of the country, and the official in charge of the Embassy was Ford’s replacement, Margaret Scobey, a new arrival in Baghdad, who had no idea of Ahmed’s value. Firas said of her, “She was really not into the Iraqis in the office.” Some Americans and Iraqis described her as a notetaker for the Ambassador who sent oddly upbeat reports back to Washington. Two days after the second interrogation, Scobey signed off on Ahmed’s termination, and ordered a junior officer named Rebecca Fong to go down to Ahmed’s office and, in front of his tearful American and Iraqi colleagues, fire him.

Ahmed later told an American official, “I think the U.S. is still in a war. I don’t think you’re going to win this war if you don’t win the hearts of your allies.” The State Department refused to discuss the case for reasons of privacy and security.

Ahmed’s firing demoralized Americans and Iraqis alike. Fong transferred out of the political section. For Firas, it meant that, no matter how long he worked with the Americans and how many risks he took, he, too, would ultimately be discarded. He began to tell himself, “My turn is coming, my turn is coming”—a perverse echo of his mantra before the fall of Saddam. The Iraqis now felt that, as Ali said, “Heaven doesn’t want us and Hell doesn’t want us. Where will we go?” If the Americans were turning against them, they had no friends at all.

Three days after Ahmed’s departure, Scobey appeared in the Iraqis’ office to say that she was sorry but there was nothing she could have done for Ahmed. Firas listened in disgust before bursting out, “All the sacrifices, all the work, all the devotion mean nothing to you. We are still terrorists in your eyes.” When, a month later, Khalilzad met with a large group of Iraqi employees to hear their concerns, Firas attended reluctantly. After the Iraqis raised the possibility of immigrant visas to the U.S., Khalilzad said, “We want the good Iraqi people to stay in the country.” An Iraqi replied, “If we’re still alive.” Firas, speaking last, told the Ambassador, “We are tense all the time, we don’t know what we are doing, right or wrong. Some Iraqis are more afraid in the Embassy than in the Red Zone”—that is, Baghdad. There was a ripple of laughter among the Iraqis, and Khalilzad couldn’t suppress a smile.

At this point, Firas knew that he would leave Iraq. Through the efforts of Rebecca Fong and Oliver Moss—who pulled strings with counterparts in European embassies in Baghdad—Ahmed, Firas, and Ali obtained visas to Europe. By November, they were gone.

JOHNSON’S LIST

On the morning of October 13th, an Iraqi official with U.S.A.I.D. named Yaghdan left his house in western Baghdad, in search of fuel for his generator. He saw a scrap of paper lying by the garage door. It was a torn sheet of copybook paper—the kind that his agency distributed to schools around Iraq, with date and subject lines printed in English and Arabic. The paper bore a message, in Arabic: “We will cut off heads and throw them in the garbage.” Nearby, against the garden fence, lay the severed upper half of a small dog.

Yaghdan (who wanted his real name used) was a mild, conscientious thirty-year-old from a family of struggling businessmen. Since taking a job with the Americans, in 2003, he had been so cautious that, at first, he couldn’t imagine how his cover had been blown. Then he remembered: Two weeks earlier, as he was showing his badge at the bridge offering entry into the Green Zone, Yaghdan had noticed a man from his neighborhood standing in the same line, watching him. The neighbor worked as a special guard with a Shia militia and must have been the alaas who betrayed him.

Yaghdan’s request for a transfer to a post outside the country was never answered. Instead, U.S.A.I.D. offered him a month’s leave with pay or residence for six months in the agency compound in the Green Zone, which would have meant a long separation from his young wife. Yaghdan said, “I thought, I should not be selfish and put myself as a priority. It wasn’t a happy decision.” Within a week of the threat, Yaghdan and his wife flew to Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates.

Yaghdan sent his résumé to several companies in Dubai, highlighting his years of service with an American contractor and U.S.A.I.D. He got a call from a legal office that needed an administrative assistant. “Did you work in the U.S.?” the interviewer asked him. Yaghdan said that his work had been in Iraq. “Oh, in Iraq . . .” He could feel the interviewer pulling back. A man at another office said, “Oh, you worked against Saddam? You betrayed Saddam? The American people are stealing Iraq.” Yaghdan, who is not given to bitterness, finally lost his cool: “No, the Arab people are stealing Iraq!” He didn’t get the job. He was amazed—even in cosmopolitan Dubai, people loved Saddam, especially after his botched execution, in late December. Yaghdan’s résumé was an encumbrance. Iraqis were considered bad Arabs, and Iraqis who worked with the Americans were traitors. The slogans and illusions of Arab nationalism, which had seemed to collapse with the regime of Saddam, were being given a second life by the American failure in Iraq. What hurt Yaghdan most was the looks that said, “You trusted the Americans—and see what happened to you.”

Yaghdan then contacted many American companies, thinking that they, at least, would look favorably on his service. He wasn’t granted a single interview. The only work he could find was as a gofer in the office of a Dubai cleaning company.

Yaghdan’s Emirates visa expired in mid-January, and he had to leave the country and renew the visa in Amman. I met him there. The Jordanians had been turning away young Iraqis at the border and the airport for several months, but they issued Yaghdan and his wife three-day visas, after which they had to pay a daily fine, on top of hotel bills. After a week’s delay, the visas came through, but, upon returning to Dubai, Yaghdan learned that the Emirates would no longer extend the visas of Iraqis. A job offer as an administrative assistant came from a university in Qatar, but the Qataris wouldn’t grant him a visa without a security clearance from the Iraqi Ministry of the Interior, which was in the hands of the Shia party whose militia had sent him the death threat. He couldn’t even become a refugee, which would have given him some protection against deportation, because the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees had closed its Emirates office years ago. Yaghdan had heard that the only way to get a U.S. visa was through a job offer—nearly impossible to obtain—or by marrying an American, so he didn’t bother to try. He had reached the end of his legal options and would have to return to Iraq by April 1st. “It’s like taking the decision to commit suicide,” he said.

While Yaghdan was in Dubai, news of his dilemma made its way through the U.S.A.I.D. grapevine to Kirk Johnson, the young Arabic speaker who had asked to be transferred to Falluja. By then, Johnson’s life had been turned upside down as well.

In Falluja, Johnson had supervised Iraqis who were clearing out blocked irrigation canals along the Euphrates River. His job was dangerous and seldom rewarding, but it gave him the sense of purpose that he had sought in Iraq. Determined to experience as much as possible, he went out several times a week in a Marine convoy to meet tribal sheikhs and local officials. As he rode through Falluja’s lethal streets, Johnson eyed every bag of trash and parked car for hidden bombs, and practiced swatting away imaginary grenades. After a local sniper shot several marines, Johnson’s anxiety rose even higher.

In December, 2005, after twelve exhausting months in Iraq, during which he lost forty pounds, Johnson went on leave and met his parents for a Christmas vacation in the Dominican Republic. In the middle of the night, Johnson rose unconscious from his hotel bed and climbed onto a ledge outside the second-floor window. A night watchman noticed him staring at an unfinished concrete apartment complex across the road. The night before, the sight of the building had triggered his fear of the sniper, and he had instinctively dropped to the floor of his room. Standing on the ledge, he shouted something and then fell fifteen feet.

Johnson tore open his jaw and forehead and broke his nose, teeth, and wrists. He required numerous surgeries on his shattered face, and stayed in the hospital for several weeks. But it was much longer before he could accept that he would not rejoin the marines and Iraqis he had left in Falluja. There were rumors in Iraq that he had been drunk and was trying to avoid returning. Back home in Illinois, healing in his childhood bed, he dreamed every night that he was in Iraq, unable to save people, or else in mortal peril himself.

In January, 2006, Paul Bremer came through Chicago to promote his book, “My Year in Iraq.” Johnson sat in one of the front rows, ready to challenge Bremer’s upbeat version of the reconstruction, but during the question period Bremer avoided the young man with the bandaged face who was frantically waving his arms, which were still in casts.

Johnson moved to Boston, but he kept thinking about his failure to return to Iraq. One day, he heard the news about Yaghdan, whom he had known in Baghdad, and that night he barely slept. It suddenly occurred to him that this was an injustice he could address. He could send money; he could alert journalists and politicians. He wrote a detailed account of Yaghdan’s situation situation and sent it to his congressman, Dennis Hastert. But Hastert’s office, which was reeling from the Mark Foley scandal and the midterm elections, told Johnson that it could not help Yaghdan. Johnson wrote an op-ed article calling for asylum for Yaghdan and others like him, and on December 15th it ran in the Los Angeles Times. A U.S.A.I.D. official in Baghdad sent it around to colleagues. Then Johnson began to hear from Iraqis.

First, it was people he knew—former colleagues in desperate circumstances like Yaghdan’s. Iraqis forwarded his article to other Iraqis, and he started to compile a list of names; by January he was getting e-mails from strangers with subject lines like “Can you help me Please?” and “I want to be on the list.” An Iraqi woman who had worked for the Coalition Provisional Authority attached a letter of recommendation written in 2003 by Bernard Kerik, then Iraq’s acting Minister of the Interior. It proclaimed, “Your courage to support the Coalition forces has sent home an irrefutable message: that terror will not rule, that liberty will triumph, and that the seeds of freedom will be planted into the hearts of the great citizens of Iraq.” The woman was now a refugee in Amman.

A former U.S.A.I.D. procurement agent named Ibrahim wrote that he was stranded in Egypt after having paid traffickers twelve thousand dollars to smuggle him from Baghdad to Dubai to Mumbai to Alexandria, with the goal of reaching Europe. When the Egyptian police figured out the scheme, Ibrahim took shelter in a friend’s flat in a Cairo slum. The Egyptians, wary of a popular backlash against rising Shia influence in the Middle East, were denying Iraqis legal status there. Ibrahim didn’t know where to go next: in addition to his immigration troubles, he had an untreated brain tumor.

By the first week of February, Johnson’s list had grown to more than a hundred names. Working tirelessly, he had found a way to channel his desire to do something for Iraq. He assembled the information on a spreadsheet, and on February 5th he took it with him on a bus to Washington—along with Yaghdan’s threat letter and a picture of the severed dog.

Toward the end of January, I travelled to Damascus. Iraqis were tolerated by Syria, which opened its doors in the name of Arab brotherhood. Yet Syria offered them no prospect of earning a living: few Iraqis could get work permits.

About a million Iraqis were now in Syria. Every morning that I visited, there were long lines outside the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees office in central Damascus. Forty-five thousand Iraqis had officially registered as refugees, and more were signing up every day, amid reports that the Syrian regime was about to tighten its visa policy and had begun turning people back at the border.

One chilly night, I went to Sayyida Zainab, a neighborhood centered around the shrine of the sister of Hussein, grandson of the Prophet and the central martyr of Shiism. This had become an Iraqi Shia district, and on the main street were butcher shops and kebab stands that reminded me of commercial streets in Baghdad. There were pictures of Shia martyrs, and also of Moqtada al-Sadr, outside the real-estate offices, some of which, I was told, were fronts for brothels. (Large numbers of Iraqi women make their living in Syria as prostitutes.) Shortly before midnight, buses from Baghdad began to pull into a parking lot where boys were still up, playing soccer. One bus had a shattered windshield from gunfire at the start of its journey. A minibus driver told me that the trip took fourteen hours, including a long wait at the border, and that the road through Iraq was menaced by insurgents, criminal gangs, and American patrols. And yet some Iraqis who had run out of money in Damascus hired the driver to take them back to Baghdad the same night. “No one is left there,” he said. “Only those who are too poor to leave, and those with a bad omen on their heads, who will be killed in one of three ways—kidnapping, car bomb, or militias.”

In another Damascus neighborhood, I met a family of four that had just arrived from Baghdad after receiving a warning from insurgents to abandon their house. They had settled in a three-room apartment and were huddled around a kerosene heater. They were middle-class people who had left almost everything behind—the mother had sold her gold and jewelry to pay for plane tickets to Damascus—and the son and daughter hadn’t been able to finish school. The daughter, Zamzam, was seventeen, and in the past few months she had been seeing corpses in the streets on her way to school, some of them eaten by dogs because no one dared to take them away. On days when there was fighting in her neighborhood, Zamzam said, walking to school felt like a death wish. Her laptop computer had a picture of an American flag as its screen saver, but it also had recordings of insurgent ballads in praise of a famous Baghdad sniper. She was an energetic, ambitious girl, but her dark eyes had the haunted look of a much older woman.

I spent a couple of hours walking with the family around the souk and the grand Umayyad Mosque in the old city center. The parents strolled arm in arm—enjoying, they said, a ritual that had been impossible in Baghdad for the past two years. I left them outside a theatre where a comedy featuring an all-Iraqi cast was playing to packed houses of refugees. The play was called “Homesick.”

In the past few months, Western and Arab governments announced that they would no longer honor Iraqi passports issued after the 2003 invasion, since the passport had been so shoddily produced that it was subject to widespread forgery. This was the first passport many Iraqis had ever owned, and it was now worthless. Iraqis with Saddam-era passports were also out of luck, because the Iraqi government had cancelled them. A new series of passports was being printed, but the Ministry of the Interior had ordered only around twenty thousand copies, an Iraqi official told me, far too few to meet the need—which meant that obtaining a valid passport, like buying gas or heating oil, would become subject to black-market influences. In Baghdad, Othman told me that a new passport would cost him six hundred dollars, paid to a fixer with connections at the passport offices. The Ministry of the Interior refused to allow Iraqi Embassies to print the new series, so refugees outside Iraq who needed valid passports would have to return to the country they had fled or pay someone a thousand dollars to do it for them.

Between October, 2005, and September, 2006, the United States admitted two hundred and two Iraqis as refugees, most of them from the years under Saddam. Last year, the Bush Administration increased the allotment to five hundred. By the end of 2006, there were almost two million Iraqis living as refugees outside their country—most of them in Syria and Jordan. American policy held that these Iraqis were not refugees, that they would go back to their country as soon as it was stabilized. The U.S. Embassies in Damascus and Amman continued to turn down almost all visa applications from Iraqis. So the fastest-growing refugee crisis in the world remained hidden, receiving little attention other than in a few reports from organizations like Human Rights Watch and Refugees International.

Then, in early January, U.N.H.C.R. sent out an appeal for sixty million dollars for the support and eventual resettlement of Iraqi refugees. On January 16th, the Senate Judiciary Committee’s subcommittee on refugees, chaired by Senator Edward M. Kennedy, of Massachusetts, held hearings on Iraqi refugees, with a special focus on Iraqis who had worked for the U.S. government. Pressure in Congress and the media began to build, and the Administration scrambled to respond. When an Iraqi employee of the Embassy was killed on January 11th, and one from U.S.A.I.D. on February 14th, statements of condolence were sent out by Ambassador Khalilzad and the chief administrator of U.S.A.I.D.—gestures that few could remember happening before.

In early February, the State Department announced the formation of a task force to deal with the problem of Iraqi refugees. A colleague of Kirk Johnson’s at U.S.A.I.D., who had been skeptical that Johnson’s efforts would achieve anything, wrote to him, “Interesting what a snowball rolled down a hill can cause. This is your baby. Good going.” On February 14th, at a press conference at the State Department, members of the task force declared a new policy: the United States would fund eighteen million dollars of the U.N.H.C.R. appeal, and it would “plan to process expeditiously some seven thousand Iraqi refugee referrals,” which meant that two or three thousand Iraqis might be admitted to the U.S. by the end of the fiscal year. Finally, the Administration would seek legislation to create a special immigrant visa for Iraqis who had worked for the U.S. Embassy.

During the briefing, Ellen Sauerbrey, the Assistant Secretary of State for Population, Refugees, and Migration, insisted, “There was really nothing that was indicating there was any significant issue in terms of outflow until—I would say the first real indication began to reach us three or four months ago.” Speaking of Iraqi employees, she added, “The numbers of those that have actually been seeking either movement out of the country or requesting assistance have been—our own Embassy has said it is a very small number.” Sauerbrey put it at less than fifty.

The excuses were unconvincing, but the stirrings of action were encouraging. When Johnson, wearing the only suit he owned, took his list to Washington and dropped it off at the State Department and the U.N.H.C.R. office, the response was welcoming. But he pressed officials for details on the fates of specific individuals: Would Yaghdan be able to register as a refugee in Dubai, where there was no U.N.H.C.R. office, before he was forced to go back to Iraq? How could Ibrahim, trapped in Egypt without legal travel documents, qualify for a visa before his brain tumor killed him? Would Iraqis who had paid ransom to kidnappers be barred entry under the “material support” clause of the Patriot Act? (One Embassy employee already had been.) How would Iraqis who had no Kirk Johnson to help them—the military interpreters, the Embassy staff, the contractors, the drivers—be able to sign up as refugees or candidates for special immigrant visas? Would the U.S. government seek them out? Would they have to flee the country and find a U.N.H.C.R. office first?

Thanks in part to Johnson’s list, Washington was paying attention. Privately, though, a former U.S.A.I.D. colleague told Johnson that his actions would send the message “that it’s game over” in Iraq, and America would end up with a million and a half asylum seekers. Johnson feared that the ingrained habit of giving yes/no answers might lower the pressure without solving the problem. His list kept growing after he had delivered it to the U.S. government, and the desperation of those already on it grew as well. By mid-March, Iraqis on the list still had no mechanism for applying to immigrate. According to the State Department, a humanitarian visa for Ibrahim would take up to six months. And Yaghdan’s situation was just as dire now as it was when Johnson had written his op-ed. “No matter what is said by the Administration, if Yaghdan isn’t being helped, then the government is not responding,” Johnson told me.

For him, it was a simple matter. “This is the brink right now, where our partners over there are running for their lives,” he said. “I defy anyone to give me the counter-argument for why we shouldn’t let these people in.” He quoted something that President Gerald Ford once said about his decision to admit a hundred and thirty thousand Vietnamese after the fall of Saigon: “To do less would have added moral shame to humiliation.”

EVACUATION

In 2005, Al Jazeera aired a typically heavy-handed piece about the American evacuation from Saigon, in April, 1975, rebroadcasting the famous footage of children and old people being pushed back by marines from the Embassy gates, and kicked or punched as they tried to climb onto helicopters. The message for Iraqis working with Americans was clear, and when some of those who worked at U.S.A.I.D. saw the program they were horrified. The next day at work, a small group of them met to talk about it. “Al Jazeera has their own propaganda. Don’t believe it,” said Ibrahim, the Iraqi who is now hiding out in Cairo.